Peace without love is only a still panic.

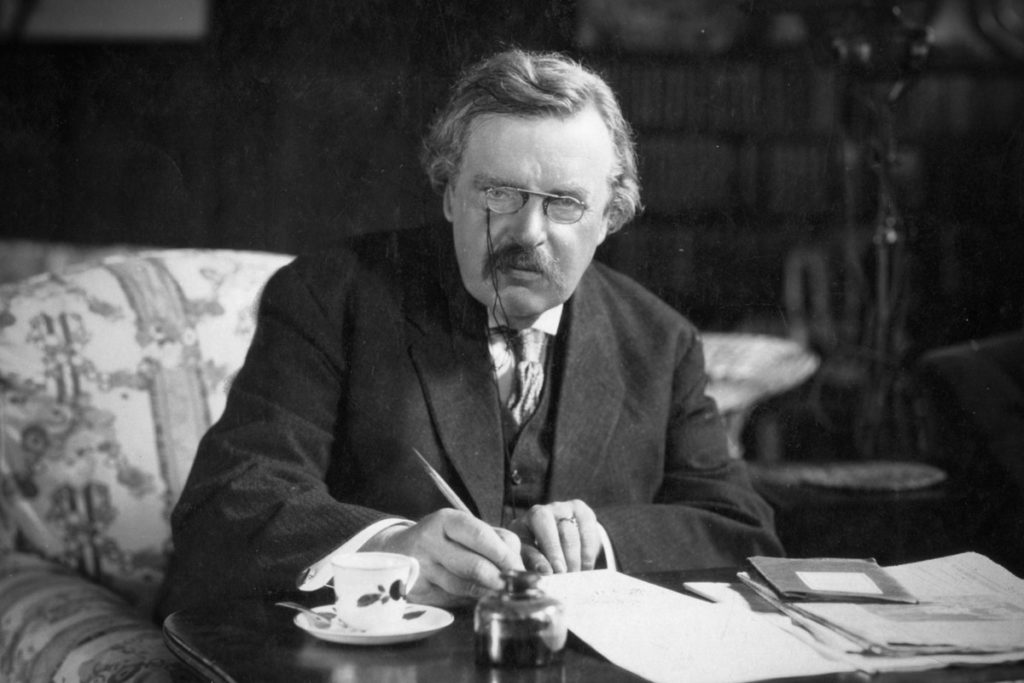

GILBERT KEITH CHESTERTON

ESSENTIAL ESSAYS FOR OUR TIME

On Being Moved

By Gilbert Keith Chesterton

From Lunacy of Letters

I am sitting and trying to write this article in a room with nothing in it except a dining-room table, a kitchen chair, and a dislocated bookcase. There are no carpets, but plenty of dust. I write with an old chalk pencil on such pieces of wall-paper, etc., as I can find lying about. I try to imagine myself to be a starving genius in a bare garret, a man brilliant, indeed, but (alas!) embittered against his kind. The illusion is periodically disturbed by the entrance of enormous men with green baize aprons who tramp in and out, taking things away. They would take my chair away but for the formidable necessity of carrying me away in it; a task from which the most enormous shrink. But sideboards and pianos melt away at their lightest gesture and bedsteads simply flee before them. Like some landslide, chair by chair … what is it that Tennyson says in the pretty lyric about Amphion? I get up and go to the dislocated bookcase to verify the quotation. But there is no dislocated bookcase. They have taken it away. I come back to my writing table and sit down again.

I wonder what the dickens I shall write about (I am not the Dickens who could write about anything); I get up again and go to the window. A white morning mist chokes either end of the road and veils Battersea Park, which I love and leave; making it like the ghost of a greenwood. I am glad it is not what people call fine weather; there is something merciful and proper in this cloud and twilight on the borderland between two lives. For the modern fate is fallen on me; I am moving into the country; I am going into exile; into England. I am going … if, indeed, I go, for all my mind is clouded with a doubt … why am I haunted with scraps of Tennyson, especially now that they have taken away the bookcase, and I cannot spell the island valley of Avilion? Avilion is a very nice place, situated in Buckinghamshire; but, like Arthur after his last battle, I feel it fitting that a vapour should veil the moment of passing; the slipping through from state to state … Tennyson again. Hades, the place of shadows of which the pagan poets sang, is not our state after death; it is simply death itself, the instant of transition and dissolution. In the end the dim beneficent powers will take the cosmos to pieces all round me, as my house is being taken to pieces now. I am glad that a cloud sits on Battersea to cover this monstrous transformation.

I go back to my writing table; at least I do not exactly go back to it, because they have taken it away, with silent treachery, while I was meditating on death at the window. I sit down on the chair and try to write on my knee – which is really difficult, especially when one has nothing to write about. I feel strangely grateful to the noble wooden

quadruped on which I sit. Who am I that the children of men should have shaped and carved for me four extra wooden legs besides the two that were given me by the gods? For it is the point of all deprivation that it sharpens the idea of value; and, perhaps, this is,

after all, the reason of the riddle of death. In a better world, perhaps, we may permanently possess, and permanently be astonished at possession. In some strange estate beyond the stars we may manage at once to have and to enjoy. But in this world, through some sickness at the root of psychology, we have to be reminded that a thing is ours by

its power of disappearance. With us the prize of life is one great, glorious cry of the dying; it is always “morituri te salutant.” [“We about to die salute you”] At the four corners of our human temple of happiness stand a lame man pointing to one road, and a

blind man worshipping the sun, a deaf man listening for the birds, and a dead man thanking God for his creation.

I begin to be moved; I perceive that there are many mysteries concealed in that kitchen chair. That kitchen chair may truly be called (as they say in the colleges) the Chair of Philosophy. I stride up and down the room, rejoicing in the divine meaning of chairs. I wave away, with wild gestures, that merely dingy and spiteful democracy

which consists in declaring that every throne is only a chair. The true democracy consists in declaring that every chair is a throne. I return rapturously to the chair; but I do not sit down in it. Wisely; because it is not there. It has been taken away. I sit down on the floor, which the enormous workmen assure me (with elephantine courtesy) they will not want for the present.

What is it, then, that makes it impossible to write anything connected or intelligible to-day? It is not mere interruption: I wrote my first criticisms of books in an office with two typewriters going at once and clerks rushing in and out every five minutes. It is not mere discomfort; I have in my youth written articles in the middle of the

night, leaning against the stall of a hot-potato man. It is not for me to say that the articles were good, but they were as good as anything else I have ever written. No; I know what it is … it is Battersea. I have the strongest and most sensible reasons in the world for going into the country. Going into the country is a joyful thing: but leaving London is a sad one. Here at least you have a harmless alphabetical paradox; one admitted by the souls of all sane men and women. It is glorious to become a man; but pathetic to leave off being

a child. It is jolly to become a married man; yet it is depressing to leave off being a bachelor. Permit to us who pass from one state to another something of the pathos that is to be permitted to those that approach to death. We are happy to go into the country, but we are unhappy to leave the town. I am leaving the most living part of London, the most romantic, the most realistic, the borough that has led the people. I am leaving the borough of Battersea. I cannot write of that; and I cannot write of anything else. When I forget thee, 0 Jerusalem, may my right hand forget its cunning; that is, let it forget how to write, in blue chalk on old wall-paper, an article about nothing at all.