As this year marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of America, it provides occasion and opportunity to reflect on how the thing has been getting along—to render up the nation’s report card, as it were. George Washington, in his first inaugural address, reflected on the prospects of the new-born country with sober foresight, setting out some of the criteria by which its success or failure might in future be judged. He noted that “there exists… an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness, between duty and advantage” and that “the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right, which Heaven itself has ordained.” He spoke of the new government as an “experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people” and surmised that “the preservation of the sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the republican model of government” might be “finally staked” on the outcome of that experiment.

These words seem to ring in the same key as the famous answer given by Benjamin Franklin, on the last day of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, to a lady in Philadelphia who had asked, “Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?” “A republic,” he answered, “if you can keep it.” This slightly ominous-sounding answer has been taken by most readers to refer to the tenuous and experimental nature of what the Founders had come up with, and the duty of preservation now incumbent upon the citizenry. It seems to me just as likely that Franklin may have been less than sanguine about the new nation’s prospects of defending itself against the Spanish, hostile indigenous land rivals, or a future attempt by the British to reclaim their wayward former colonies. In any case, whether intended by its speaker or not, the former meaning has stuck, and it is the one that resounds with significance for us today.

So, how have we been doing these 250 years? Have we kept the republic well? Elsewhere in his inaugural address, Washington expressed confidence that the new government would remain free from “local prejudices or attachments” as well as “separate views [and] party animosities.” Well, we’ve certainly made a proper pig’s ear of things there, at least, so let’s chalk up a few demerits in that column. How about the “indissoluble union between virtue and happiness”? A decade after Franklin’s witty repartee with the woman in Philly, then-President John Adams warned an audience of militia that, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” Alas, here, too, it’s hard to give full marks.

Chesterton wrote that “this world is all one wild divorce court,” and certainly the world of specialists and technocrats he was railing against has tried its best to sunder the “indissoluble union” of virtue and felicity. This is nothing new, nor even was it new in Chesterton’s day. Jeremiah knew that the wicked may prosper in this vale of tears; so did Chesterton’s beloved Job. Psalm 92 carries the observation that “the wicked spring as the grass” and “all the workers of iniquity do flourish;” and, according to a Talmudic tradition, this psalm was composed by Adam in the Garden of Eden on the seventh day! Talk about honeymoon jitters. So, yes: nothing new, indeed. We all know that as billionaires boldly sin their bottom lines grow, while the lists they apparently keep of their fellow miscreants get buried by bureaucrats either too timid to punish them or themselves compromised by complicity. As for the common man, well, he oftentimes fares no better. Chesterton knew certain conditions must attain for the maintenance of a virtuous and prosperous peasantry, and he lamented that the modern age every day whittled away at the posts supporting that once sturdy structure. As men become vicious, society suffers for want of the necessary virtues for justice and peace; and, in its turn, a society so degraded vitiates those of successive generations of its citizens, and the whole becomes a looping, downward spiral.

And yet… There is grace, always and everywhere, even all the more where sin abounds. It is a mystery, wonderful to behold, far more than we deserve, and more than sufficient for our need. The culture may lose its head, but we can keep our own: or, at least, if we’re bound to lose them, we can lose them only as John Fisher and Thomas More would, counting our loss so much gain. The blood of the martyrs is ever the seed of Christians.

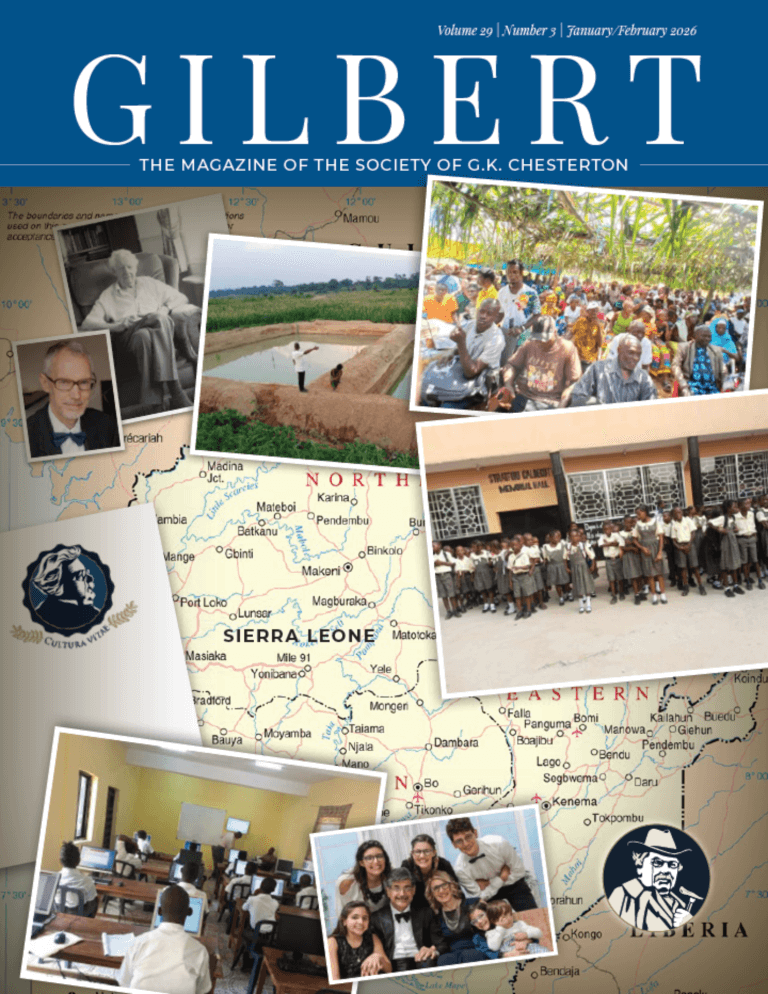

Planting seed: that is what we must be about. It is what we at the Society of G. K. Chesterton are about, most especially through the Chesterton Schools Network. Whatever our nation’s Founders might have gotten wrong, they got this right at least: the common weal begins with the common man and his ordinary life of virtue. The strength of a nation depends upon its foundation in the family; the home’s prosperity is the measure of the homeland’s. Man must first look to his soul, and only then can society benefit from him.

We don’t know what the next 250 years will hold for the “experiment” that is America. Our task may be to build to new heights. It may be merely to bank the fires against the onrushing night, or to rebuild from the ashes after some great cataclysm. However it may be, such will only be the circumstances in which we, or our children, or our children’s children, have to do what is in every circumstance the duty of Christians: serve God, and love one another. We must plant, cultivate, and grow the virtues in ourselves and in the next generation entrusted to us, and that will be enough for facing whatever the future may hold. We may not be able to keep the republic. We may not even be able to keep our heads. But we’ll keep our souls.