Next year, the United States will celebrate its Semiquincentennial, or 250th anniversary. Per Wikipedia, other names under which this occasion is being heralded include “Bisesquicentennial,” “Sestercentennial,” “Quarter Millennium,” and—inspired, no doubt, by the advertising and marketing fads of late capitalism—the banal “America250,” which sounds more like a software suite than a memorial.

The date of July 4, 1776, seems universally to be considered the “birthday” of the nation. Yet, just as in the case of any man and his own birth, this highly remarkable and very visible occasion isn’t the beginning of the life of the creature. The life of any animate body, in spite of what many of our culture’s ideologues and politicians might hold, begins at the moment of conception. It is, however, far more difficult in the case of a nation, compared to the case of a person, to determine when conception has taken place.

2025 has already marked several of its own significant semiquincentennials of the American Republic. April 19th marked 250 years since what Emerson called “the shot heard round the world,” when “the embattled farmers” of the Massachusetts militia began the bloody conflict with the British in the battles of Lexington and Concord. May 10th marked the 250th anniversary of the capture of Fort Ticonderoga by the Green Mountain Boys, led by Benedict Arnold (before he became a traitor) and Ethan Allen (before he became a furniture store).

June 14th may be an anniversary more familiar to most, since this year’s observances of it were marred by a certain amount of political controversy. Yet, I wonder whether even a third of those aware of the commotion over the parade in the nation’s capital are familiar with the occasion it was held to commemorate: the birth of the U.S. Army via the establishment of the Continental Army and the appointment by the Second Continental Congress, the following day, of George Washington as our nation’s first commander-in-chief.

It was the kerfuffle connected with June 14th that started me ruminating on the fact that America’s Semiquincentennial really is a series of so many semiquincentennials. Yet the prior anniversaries in the year had passed with little if any notice at all. Indeed, for that matter, so had June 14th: The historic date it recollected was lost to observation in the steam of vapours generated by so much hot air emitted from commentators on both sides of the political aisle, who seemed to think the day should be about our current, rather than about our first, president’s legacy.

I am a patriot, in my own way; or at least I try to be. I love the rolling hills of Pennsylvania where I was born and raised, as well as the historic cobbled streets of Philadelphia near to where I live now. I hang out flags in the appropriate season, and even eat the occasional hot dog when the national rites prescribe, though I’m much more a fan of that comestible’s German ancestors than I am of their flaccid pink American scion. I am certainly no jingoist, however, neither in the present nor about the past and future. I’ve been known to take an undue degree of pleasure from stoking controversy amongst co-religionist friends at a July 4th picnic, by opening a debate as to whether the American Revolution meets Catholic theology’s standards for a Just War. I’ve had great fun arguing both sides. “What is your real opinion?” First, you tell me yours. Why miss the chance of a good argument? And maybe, in the end, I’m not really sure anyhow. But I like to think that this is because of, and not in spite of, my patriotism.

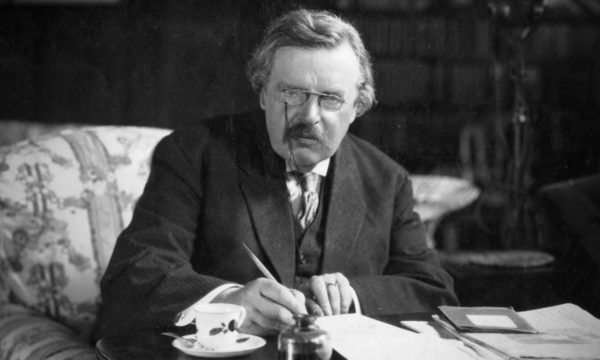

I derive the model of my patriotism from Chesterton, who, in Orthodoxy, contrasts mere “optimism” with a true “patriotism.” In context, he is speaking about what he calls “cosmic patriotism,” the approach one ought to take to the whole universe. Yet, his analysis works on the smaller scale just as well. He writes, “The point is not that this [place] is too sad to love or too glad not to love; the point is that when you do love a thing, its gladness is a reason for loving it, and its sadness a reason for loving it more. All optimistic thoughts about [the homeland] and all pessimistic thoughts about her are alike reasons for the… patriot.”

The question for the patriot is not, Chesterton says, a matter of “criticism or approval,” but rather of a “primary loyalty.” This loyalty sometimes calls forth approval, to be sure; but it just as well may at other times demand criticism. Both are born of the same spirit: love. The love of one’s native place. And love, philosophy and the holy doctors teach us, consists in willing the good of the other. “Men did not love Rome because she was great,” Chesterton observes. “She was great because they had loved her.” So any place, any nation. The patriot isn’t the person avowing foolishly that such and such a place is beautiful in spite of all the rubbish that may be lying about. Nor is he the one merely complaining about the rubbish and castigating the place for being ugly. The patriot is the one picking up the rubbish – perhaps all the while lamenting that the place has indeed in ways become ugly – but only because he loves it.

It is lamentable that some of our semiquincentennials have passed either without notice or else eclipsed by the shadow of bickering to score political points. In the first place, it has robbed us of the fun of getting to try to say “semiquincentennial” more often. More seriously, though, it has robbed us of so many opportunities to reflect on what constitutes a proper patriotism: what it demands with respect not only to the present, but to the past and future as well.

I remarked on the difficulty of defining the moment of conception of a nation. Maybe it really is no easier to define the date of birth, in spite of what the calendar may tell us. Perhaps this is because both really are not discrete moments at all, but processes: ongoing processes which constitute the real work of the true patriot. This may have been part of the gist in Lincoln’s great address at the battlefield of Gettysburg, where he remarked on the nation’s conception and asked whether a nation so conceived could long endure. That nation was still being conceived in the hearts of her citizens at that time, amidst a bloody war. She was still being born, and the battle lately fought there was the most anguished of labor pains. These processes, those pains, continue in the present; and their outcomes will determine the shape of the nation yet-to-be-born in the future. The patriot, critic and admirer both, yet never merely one nor the other, takes for his sacred duty to see to it that a more stable peace and a more just polity be born alongside future generations of citizens. It will be born of his primary loyalty, of his own sweat and tears and possibly even blood, offered not because the nation is or has been perfect, but offered out of love for a thing that may yet become more perfect. Inasmuch as they remind us of this solemn fact, I don’t think we really can get enough of semiquincentennials.