Guys of a certain vintage have a favorite bragging rights contest. It begins with, “We had it really bad when I was young,” followed by gritty, liberally embellished details of some near apocalypse in early life. The finishing touch is a smug, dismissive comment about the weak-pulse and sedentary lives of “young people these days.”

These competitions reach feverish extremes when the faux, former men of steel trot out a parade of horribles about summer jobs they endured in high school and college.

I regularly bluster my way to the medal round in this “summer jobs from Gehenna” contest. I paint vivid pictures of debilitating stabs of lower back pain from picking rock in corn fields and lament a summer sweating alongside Attila the Hun lookalikes on a road construction crew. I describe loading trucks in 90-plus degree conditions and lifeguarding at a time before dermatologists announced that my lobster-red sunburn would be an invitation to you-know-what in later life. I close with a flourish, citing my summer as a humanoid machine on a repetitive-motion factory assembly line.

But in the future, this sort of sentimental bravado will be confined to an ever-dwindling number of the increasingly geriatric.

Since 1948, as far back as the data goes, the teen summer employment rate has fluctuated between a low of 46 percent and a high of 58 percent, according to the Pew Research Center. Beginning in the 1990s, however, the number of teens with summer jobs dropped off a cliff, coming in at 31 percent in 2024. The rate for 16- to 17-year-olds was under 20 percent – less than half the level for that group as recently as 2000.

Why are summer jobs going the way of the buffalo?

Many families – mine included – considered that a summer job could make a serious dent in paying college costs, but summer income is now a drop in an ever-more-gigantic bucket. The average cost of tuition has increased nearly 180 percent in the past 20 years, even after accounting for inflation.

Many students now opt to spend summers “resume building,” with internships or special classes that burnish career credentials. Fast food and lawn mowing jobs just don’t have the same panache as a summer class in “international relations” or a non-profit internship in “saving the rain forests.”

Teens with sports interests increasingly believe that, to have a shot at making varsity, they must load up their summer with leagues, camps, and individualized training – a blizzard of activity that doesn’t match well with the scheduling regularity that most summer jobs require.

Are young people increasingly unwilling to take on often-tedious summer work, given the video game’s invitation to an exhilarating fantasy world and the addictive buzz of the social media hive? On average, 15- to 18-year-olds devote seven-and-a-half hours a day to entertainment screen time. That doesn’t leave many summer hours for loading trucks or serious nannying.

So, are summer jobs destined to become nothing more than wistful, Norman Rockwell-like memories to an ever-smaller number of the graying set? Perhaps, but before we allow them to fade and die, it may be worth taking a second look at a few of the reasons we once held them in high esteem.

A summer job provided many teens with their first opportunity to learn what it takes to operate successfully in the larger world. Work outside the family usually entailed accountability to an unsentimental, cost-benefit-minded boss with no interest in slackers and employees who show up late. Service work taught young people what it means to “look your best” and to make confident, cheerful eye contact, even when dead tired and the customer they were assisting was the 83rd person to whom they’d served a hamburger that day.

If young people don’t develop these skills in their teenage years, they may be harder to acquire in their 20s and 30s. Is there a connection between the disappearing summer job and 20-somethings – notably young men – lingering in dependency on parents and others well into their adult years?

In addition, my dad’s summer-job motivator still rings true: “You’ll learn the value of money, son.” Who can forget the pride of being handed that first paycheck after two weeks of exhausting summer work? I spent those dollars as if they were precious jewels. I still recall regarding the college books I bought with those dollars as akin to sacred texts.

What a different message is sent if Mom and Dad demand no gas contribution for the family car, don’t expect the kids to spring for their own movie tickets and music, and underwrite a college experience that requires no financial sacrifice from the student.

For me, summer jobs also offered an opportunity to break out of the insular intellectual world I entered after high school. Like many college students, I lived almost exclusively in the realm of the theoretical. In that rarified atmosphere, I was inclined to genuflect at the altar of the latest “save-the-world” ideas. These fashionable preoccupations – war and peace, societal inequalities, race relations, distribution of wealth – were always presented on a macro scale, empty of any conception of human nature, especially original sin. And they were always marked with a strong dose of condescension toward the unenlightened.

I also lived in college life’s late-adolescent bubble – socializing with others our own age, all meals served to us in the cafeteria, and responsible for no one but ourselves. I had little opportunity to experience the adult world of struggles with families, jobs, sin, redemption, and faith. I recall often gazing into the distance from my upper-story dorm window at the rows of houses and individuals going about family life off campus. I had the vague sense that they inhabited a foreign country.

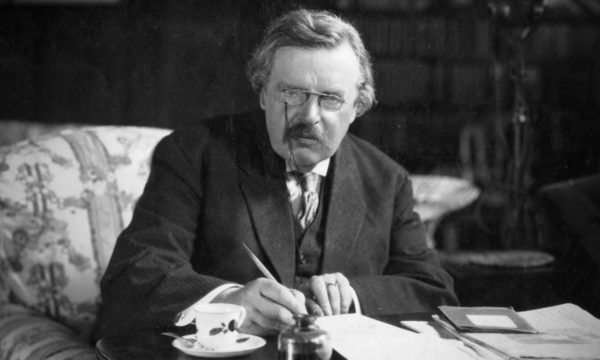

My summer coworkers in the factory often expressed disdain for me (“What are you doing here, college boy?”), knowing I would go back to my academic thought-clouds in September. I bristled at this label. But as I worked alongside them, I came to see they had some things to teach me – the bookish life needs a regular check-up in the factory lunchroom where virtues and vices, unfiltered through textbooks, play out through the stuff of Adam’s flesh. I learned that talking about wisdom was not the same as being wise. Or, as G.K. Chesterton might have approvingly noted, I began to appreciate the ordinary person as a potential bearer of deep, intuitive truths that intellectual elites often overlook.

Gary Saul Morson, a professor of Slavic Studies, writes that the great Russian novelists – Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Solzhenitsyn, and others – fought back against the grand schemes of the university crowd, which disdained small acts of kindness at workplaces and in other social settings. “Radicals of Dostoevsky’s time,” wrote Morson, “despised what they called ‘small deeds,’ such as one person charitably helping another because, they maintained, only total social transformation could overcome evil.” These extraordinary novelists affirmed the value of decency outside the bounds of ideology.

The hero of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Pierre Bezukhov, initially chases after grand theories to use as models in charting the best life. After numerous failures, he recognizes the blessedness of ordinary life before his eyes in his own home. These everyday blessings and family relationships are not just incidental markers toward a grand historical goal but holy and life-giving in themselves, he learns.

My summer work suggested to me that many clues to the good life could be found by seeking that “blessedness” in the lived lives of those in my immediate presence – and that new understanding began to temper the siren-song of my theoretical pursuits.

These hints about what’s at the heart of the fully human life were, perhaps, the greatest gift that is now being lost with the disappearing summer job.